I Will Visit Ahok in Prison One Day, Says NU Cleric As’ad Ali

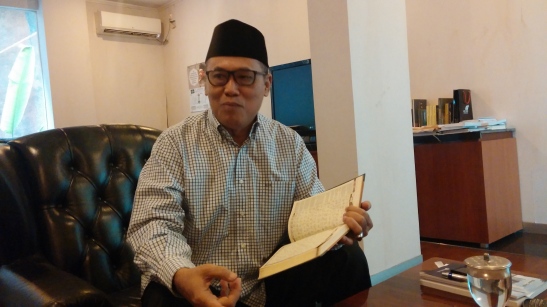

Prominent Nahdlatul Ulama cleric As’ad Said Ali during an interview with the Jakarta Globe at his office in South Jakarta on Thursday (10/08). (Photo courtesy of Amal Ganesha)

Jakarta. Radicalism is often interpreted as a fundamentalist approach to religion through a strict, literal interpretation of scripture. The word has been heavily associated with hardline Islamist groups since the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks but in Indonesia it has a more nuanced meaning.

When the former governor of Jakarta, Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama, was jailed in May for blasphemy, there were concerns that religious tolerance in Indonesia was at a historic low.

Ahok, a Christian of Chinese descent, was sentenced to two years in prison after judges found him guilty of having committed blasphemy by quoting a verse in the Koran in an attempt to settle the question of whether Muslims are allowed to elect a non-Muslim leader.

Some argued that Ahok’s blasphemy case reflects an ever-widening crack in the supposedly Indonesian value of Bhinneka Tunggal Ika, or Unity in Diversity, and questions citizens’ loyalty to the state ideology of Pancasila, which prescribes pluralism.

The administration of President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo seems to have been preoccupied with the issue of radicalism and it came to a head in the government’s decision to disband Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia (HTI), the local chapter of an international pan-Islamic organization that has been pushing for the establishment of a caliphate in the archipelago through non-violent means.

“[Nahdlatul Ulama] has been a firm supporter of Pancasila, HTI has not. Both of us are concerned with ijtihad [finding solutions to legal questions], which is good in itself, but [preservation of] the state must always take precedence,” As’ad Said Ali, advisory board member at NU, Indonesia’s largest Muslim organization, told the Jakarta Globe during an exclusive interview at his office in South Jakarta on Thursday (10/08).

“I will visit Ahok in prison one day; he’s a man of intellect,” As’ad said.

“Ahok being a Christian is a non-issue for me, but he had crossed the line by offering his own interpretation of that Koranic verse. That hurt many Muslims.

“Had Ahok never said anything about the Koran, he would’ve won the election,” As’ad added.

Pancasila’s Forgotten Shariah Article

Pancasila became Indonesia’s official state ideology on Aug. 18, 1945, a day after the country’s founding father, Sukarno, issued a declaration of independence during the final days of the short-lived Japanese occupation.

Sukarno was able to convince his political allies that recognizing diversity would be key to uniting the newly independent country. The first tenet in the current version of Pancasila states, “belief in one God,” which is generally interpreted as a political, pluralist call to arms that guarantees Indonesians of all faiths the right to worship.

But a previous draft of Pancasila, known as the Jakarta Charter, existed as part of the introduction to Indonesia’s 1945 Constitution, written in Jakarta during June of that year by the so-called Team of 9, including Sukarno.

The first tenet in the Jakarta Charter said, “belief in one God, with an obligation for all followers of Islam to practice shariah.” The proviso did not make it to the final version of the Pancasila.

Since then, many radical Islamic groups have attempted to reimpose shariah in Indonesia, either through non-violent political means, or through violent attacks against the state.

Radicalism Is Not Terrorism, but Pretty Close

According to As’ad, there is a fine line between radicalism and terrorism. Radical groups – like the recently banned HTI – do not always use violence to achieve their goals, while terrorist groups such as Al Qaeda by definition place violent struggle above anything else.

In Indonesia, a group can also be deemed radical if it does not adhere to the Constitution or Pancasila.

National Counterterrorism Agency (BNPT) head Comr. Gen Suhardi Alius said radicalism is only a step away from terrorism. Once an individual is radicalized, he or she could easily be convinced to carry out terror attacks.

Meanwhile, in a Jakarta Globe article published in July, professor Haroon Ullah of Georgetown University claimed that some Indonesians approve and even become involved in terror attacks because they are disillusioned with the chaos and corruption that they see around them every day.

As’ad concurred by saying that corruption creates inequality, which is one of the biggest stumbling blocks to democracy in Indonesia.

“As long as inequality remains significant in society, democracy will never take root,” he said.

Indonesia’s Gini ratio, used to measure the level of inequality, stood at 0.393 in March this year, slightly worse than in 2014, when it was 0.381. That placed Indonesia at the time as the country with the fifth-worst inequality index in Southeast Asia. A Gini coefficient of zero expresses perfect equality, while a value of 1 expresses maximal inequality.

Fighting Radicalism With Soft Power

In a speech at Airlangga University in Surabaya on Aug. 2, As’ad pointed out that Islamist groups which mushroomed in the early part of this century – Islamic State and Al Qaeda for example – were becoming more revolutionary than earlier groups such as Hizbut Tahrir. They also increasingly rely on terror attacks to advance their cause.

He said both the government and radical Islamist groups are staking their claims on Pancasila, trying to use it as justification for their actions.

As’ad believes attempts to create and Islamic state or a caliphate in Indonesia must be countered with strict law enforcement, but without the same repressive actions employed by Suharto’s so-called New Order regime. The government should rely more on “soft power” – encouraging Indonesians, especially students, to counter the spread of radicalism.

Nahdlatul Ulama’s Role

NU was established in 1926 by Hasyim Asy’ari, the grandfather of Abdurrahman Wahid, the country’s fourth president. The organization established Indonesia’s first educational institutions based on Islamic teachings during Dutch colonial rule.

NU currently operates more than 16,000 Islamic boarding schools, or pesantren, offering basic education from primary to secondary levels.

The organization also has more than 700,000 mosques owned and operated by its members.

“NU grew organically. Our dakwah has always been focused on preserving tolerance,” As’ad said.

To accusations that NU may have lost its power to resist hardline groups, As’ad said: “It’s the state’s responsibility to maintain tolerance, not ours. But if the government want to do more about deradicalization, one of the easiest ways is to support NU because we’ve been fighting hardline groups from day one.”

One of the largest hardline groups, and one that fought hard to have Ahok convicted, is the Islamic Defenders Front (FPI).

“An organization like the FPI can be useful,” As’ad said.

“As Muslims, we have to practice ammar ma’ruf nahi munkar [prescribe what is right, proscribe what is wrong], but the FPI had just gone overboard doing the latter. That has done a lot of damage to their image.

“Many FPI members are also members of the NU. NU members are free to join other organizations, even HTI.

“Rizieq Shihab [the fugitive leader of the FPI] is my friend. I think what happened to him is not right. I think there has been a conspiracy against him. It’s not good.”

The former deputy chief of the State Intelligence Agency (BIN) believes the state should avoid playing off radical groups against more moderate ones.

“The prerequisite for tolerance is, if we see differences, don’t highlight them,” As’ad said.

Reporting and Writing by Amal Ganesha and Muhamad Al Azhari for the Jakarta Globe

Recent Comments